Every industry has an oligarchy. These are experts whose organizations can afford to send them to the meetings, tie them up for weeks preparing and participating, processing the travel reimbursements and then wait for 6 to 12 years for tangible results. In some deep cycle industries — such as the energy and pharmaceutical industry — long lead times like this are commonplace (and necessary). Not so for the nearly $500 billion education facility industry; the largest non-residential building construction market in the United States. You can see the result in the parabolic increase in the cost of education. Taking 1-2 percent off that $500 billion annual spend would be meaningful in any industry but the US education “industry”.

Still, we soldier on

Question: Who are “Incumbent* Stakeholders”?

Answer: Note that throughout this site we often use the term “vertical incumbents” or “niche verticals” to describe the non-profit organizations who claim a “silo” of expertise.

In relative order of strength — ranked from strongest to weakest:

-

- Conformity & Compliance (insurance, inspection); conformity & compliance trade associations

- Labor; labor unions, non-profit organizations that service the labor unions

- Manufacturers (organizations that produce hardware, software, middleware and sometimes installs it); non-profit manufacturer trade associations

- Installers (contractors who install products and sometimes operate and maintain them); contractor trade associations

- General Interest (government, legal professionals, building design professionals, communications consultants)

- Users (the final fiduciary; in our case, the education facility industry) who provide a ~$500 billion market to all of the foregoing. Many education industry trade associations depend upon membership and conference sponsorship from the first five on this list. Like all the other interest groups, they go where the money goes so we exclude education facility industry trade associations as a pure user interest.

Even though the US standards system requires 1/3rd participation by the User Interest (See ANSI Essential Requirements: Due process requirements for American National Standards); it is rare to find standards development committees that meet the ANSI criteria for balance representation. The lack of balance is usually not the fault of the standards developer.

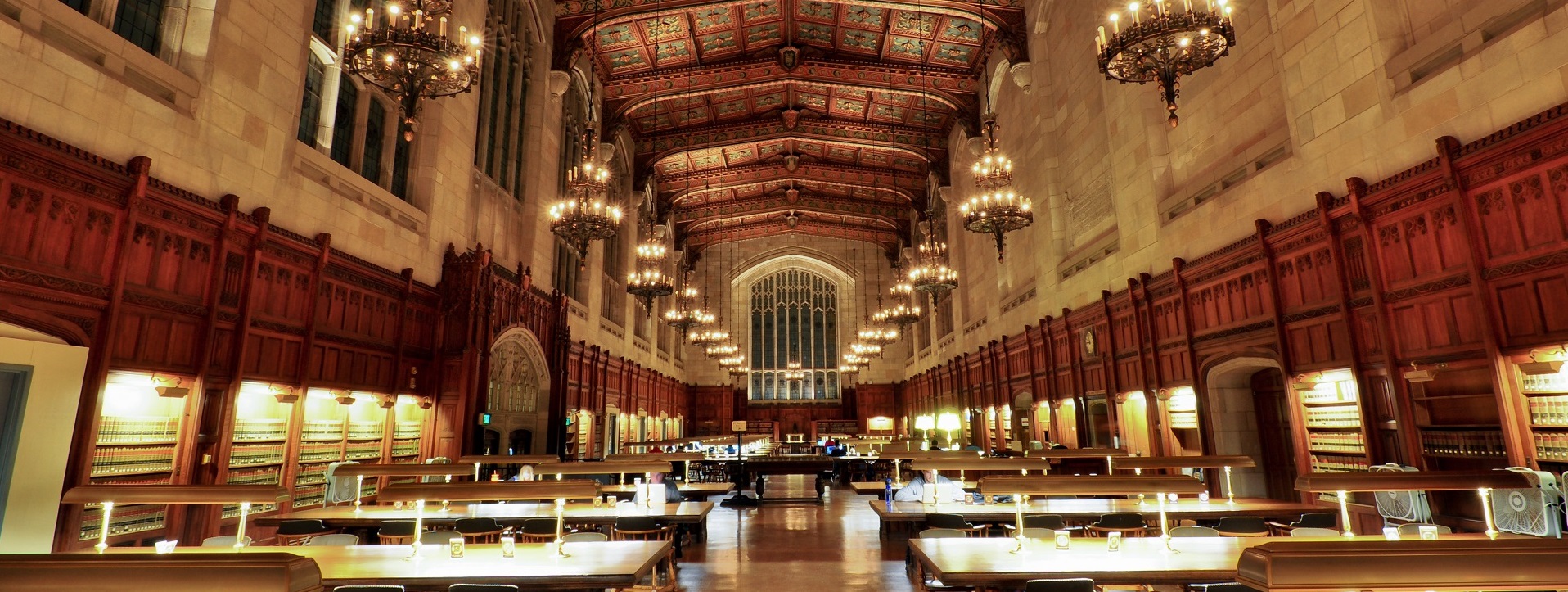

Incumbent stakeholders are able to finance their participation in codes and standards development because they can build the cost of their advocacy — professional time, travel, legal support — into the product or service they sell to the user interest. One need only review the roster of technical committees of accredited consensus standards developers to discover who can afford to attend the face-to-face meetings; sometimes in lavish venues. Informed voices in the education industry — largely a sector that depends upon highly regulated public money — are almost never supported by upper management to attend these meetings.

A great deal of the ~$500 billion education facilities market in the US is built with components that originate with Producers and General Interests from all over the globe — multinational industrial conglomerates with sectors diversified across economic cycles. Fair enough. What is not so fair is that those face-to-face meetings are attended by the same people with the same titles. We never see the foreman of the elevator shop, overseeing the better part of one-thousand elevators on a typical research university campus, at the elevator standards development meetings, for example. You will find the standards administrator there, or the chief of standards development there, but you rarely find the person with the operating data and the workpoint experience at that meeting. We believe he or she should be.

We do not make a large fuss over it because we want to be “collegial” and to fit into the rather rarefied space of the global standards federation. Almost everyone we know in the global standards federation is well-meaning; nearly to a fault. Idealistic, even. It is very difficult explaining to the business officer or CFO of a large research university to invest in cost avoidance. Revenue coming in the door is easier to count and tracks well in trustee meetings. In other words: No one knows how to count something that does not happen. We can only see its absence lifting the cost parabola. Furthermore, unlike deep cycle industries such as the energy and pharmaceutical industry that nurture a portfolio of R&D opportunities over decades, the leadership of the US education facilities industry cannot support investment that pays off in 9 to 12 years when their bosses — college presidents — are not likely to be at the helm of the university that long.

To be fair, all standards developers do reach out to user-interests. They do so every week in ANSI Standards Action and elsewhere. It is not the fault of incumbents if the user-interest is distracted, overwhelmed by other priorities, or simply does not know. As the CEO of ANSI explains in the clip below, the higher up you go in an organization, the less is understood by senior leadership.

That much said, we are fond of saying: “Standards are the seed corn for compliance revenue”. No one gets in the standards business to make money writing, publishing and promulgating standards. Standards development is expensive and confounded by copyright laws. Intellectual property claims are a minefield of sensitivities. Competition among the top tier of standards developing organizations is fierce — especially in emergent technologies in which standards developers seek to make markets in training, conference/hosting and conformity/certification enterprises. Incumbent interests get into the standards business — after considerable investment in developing intellectual property — to recover that investment by making money by enforcing the standard; or training those who will enforce the standard.

To a large degree the education industry itself is a compliance and conformity industry because it sets criteria for establishing benchmarks for educational achievement. Standards Michigan’s primary objective is to reduce redundancy and destructive competition among the 100,000-odd colleges, universities and school districts in the United States who are spending at an annual rate of about $500 billion (with meaningful outreach and collaboration with like-minded education industry professionals in other nations). It can be a lonely business because most of the US education industry “culture” is built upon social conformity, risk-aversion and the palliative effect of well-above-average employee benefits.

Still, the global standards system has the practical effect as a “shadow government” for technology development and regulation. We do not want to see summer interns working summer jobs for a US Congressman or Senator writing drafting federal legislation for distributed, decentralized, public ledger (blockchain) technologies. There are many consulting organizations domiciled in the Washington D.C. area that would like it that way but we do not.

The “Constitution” of the US standards system — which resembles the standards systems in other nations — is linked below. See Section 2 for interest categories (Producer – General Interest – User)

ANSI Essential Requirements: Due process requirements for American National Standards

User interests — in our case, the education industry; a large public sector user interest — we are interested in avoiding cost; a far less glamorous undertaking than making money. In the public sector, the money spent is “everybody’s money” so there is far less incentive to exert downward pressure on #TotalCostofOwnership.

To repeat: ANSI does require that accredited standards developers reach out to populate committees with a balance of interests. Every week those standards developers are shouting from the mountaintops for volunteer User Interest committee members but we find that the individual institutions and trade associations do not finance expertise. Some of them are prohibited from participating in what is perceived as direct lobbying. Some of them depend upon the revenue incumbent interests that are instructed to vote against the user interests.

This is why we refer to the debacle of the user-interest as a “wicked problem”; or, more generally, the central problem of participatory democracy.

It is a complicated story and one that we discuss during our monthly review of education industry trade association advocacy activity. See CALENDAR for login information.

*We adapt the term “incumbent” from a 2012 Harvard Business Review article: “How Corruption Is Strangling U.S. Innovation” by James Allworth. While we do not agree with everything in the article, we do have front line experience — in the hurly-burly of standards setting — in which the USER-INTEREST is overwhelmed by competitor interests with deep pockets for marketing and/or advocating regulations rather than taking risk with innovation.