The global dental industry market is relatively small in relation to that for health care in general, but it is a lucrative and highly competitive market. The global dental market is estimated for the 2017 – 2018 financial year to be worldwide US$31.5 billion. For 2021, the scale of the global dental market is predicted to be around US$37 billion and growing with the population. We keep pace with action in dentistry best practice literature because many higher education institutions have significant dental health education enterprises. The physical assets that support them are relatively complex; usually involving research, instruction and clinical delivery.

Strategic Business Plan ISO/TC 106

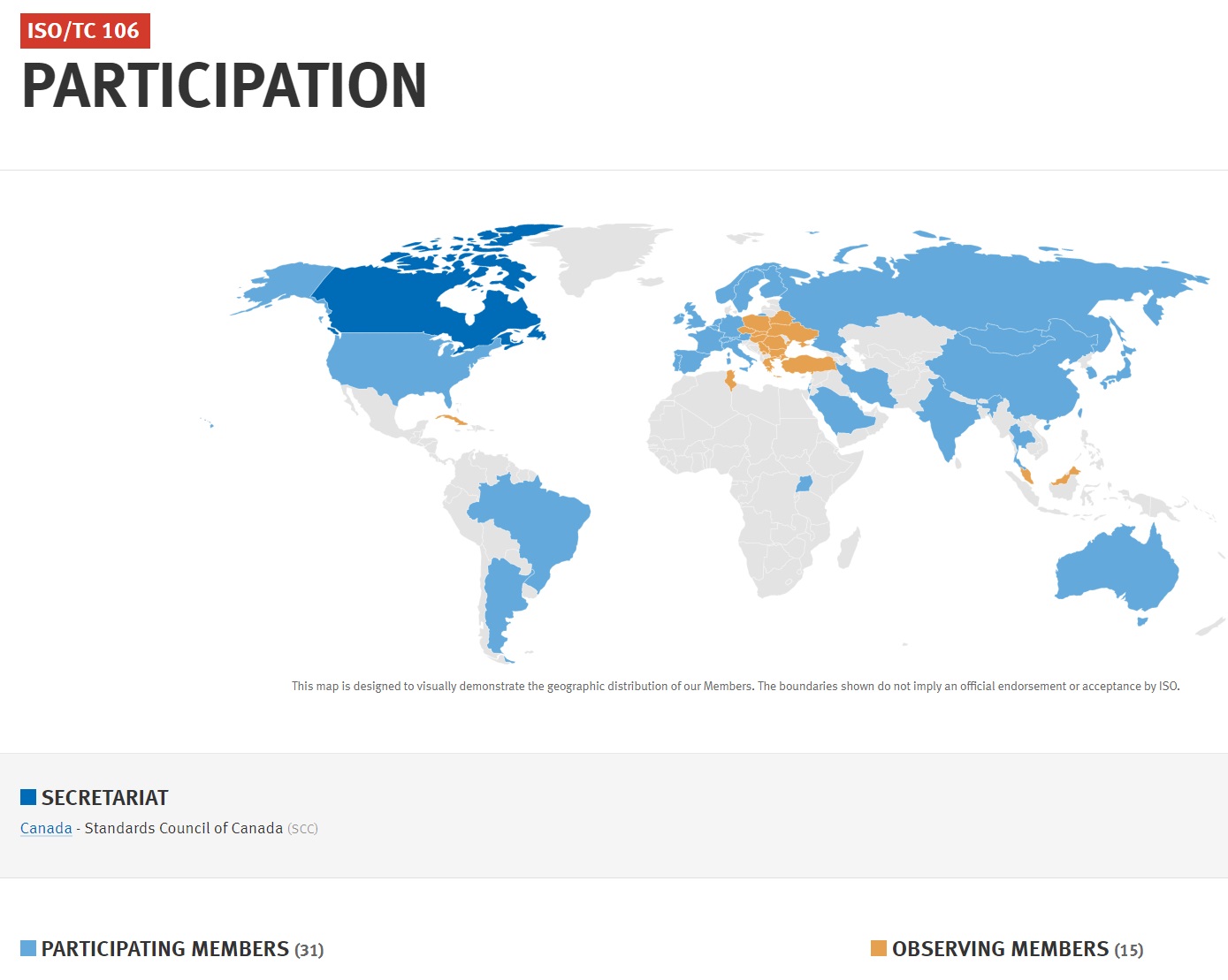

Canada is the Global Secretariat. The United States NSB is the American National Standards Institute and the US Technical Advisory Group Administrator is the American Dental Association.

Home Page for US TAG for ISO/TC 106 Dentistry

The U.S. TAG is comprised of eight Sub-TAGs which are responsible for a particular broad category of standards. They are:

- Sub-TAG 1: Orthodontic & Restorative Materials

- Sub-TAG 2: Prosthodontic Materials

- Sub-TAG 3: Dental Terminology

- Sub-TAG 4: Dental Instruments

- Sub-TAG 6: Dental Equipment

- Sub-TAG 7: Oral Care Products

- Sub-TAG 8: Dental Implants

- Sub-TAG 9: Dental CAD/CAM Systems

Like nearly every US TAG, the ADA welcomes experts — particularly experts from the Consumer (User) point of view. The next US TAG Meeting will be held July 19-21, 2021 in Boston. Contact Kathy Medic at medick@ada.org for details.

The next annual ISO/TC 106 meeting will be held August 29 – September 3, 2021 in the U.S. at the Loews Coronado Bay Resort in San Diego, CA. More than 350 delegates comprised of dental product manufacturers, dentists, researchers, educators, government/regulatory agencies, and professional dental associations from over 30 member countries attend this important yearly meeting. More information will be posted as it becomes available. Members of the U.S. TAG are encouraged to attend. To find out more information, please contact Kathy.

We break down action in dentistry standards several times a year. See our CALENDAR for the next online meeting; open to everyone.

Issue: [12-81]

Category: Health, Global

Colleagues: Mike Anthony, Christine Fischer, Jack Janveja