Standard stitch work – standards for men’s clothing sizes trace back to the Civil War, but no one even attempted to fix the sizes for women until almost a century later, when they called on NIST. #NYFW pic.twitter.com/dFQVGknU3w

— National Institute of Standards and Technology (@NIST) February 13, 2021

Tag Archives: May

- Home

- Posts tagged "May" (Page 3)

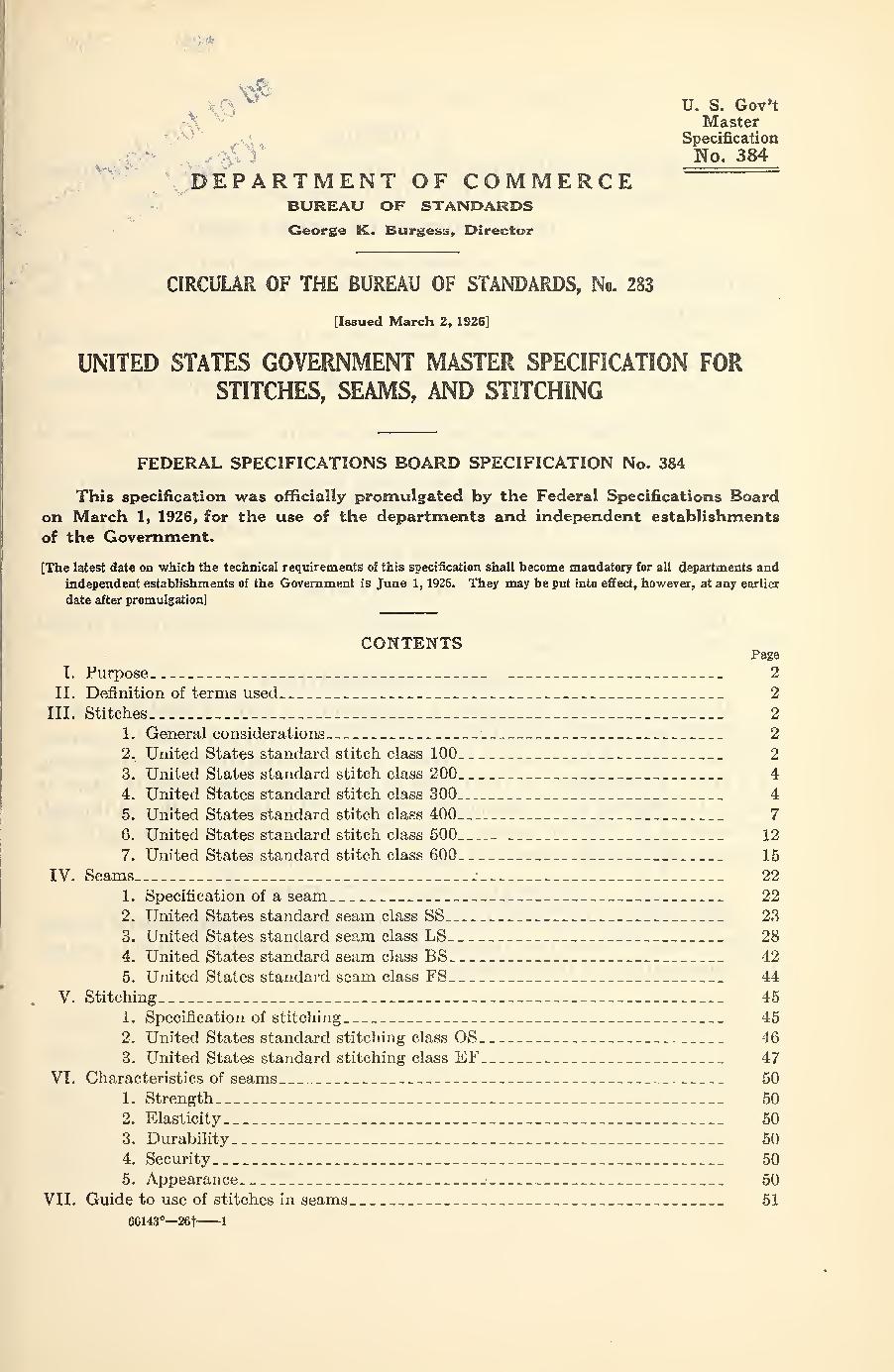

Stitches, Seams & Stitching

El Paso

This content is accessible to paid subscribers. To view it please enter your password below or send mike@standardsmichigan.com a request for subscription details.

“Fanfare for the Common Man”

This content is accessible to paid subscribers. To view it please enter your password below or send mike@standardsmichigan.com a request for subscription details.

Homeland Power Security

We collaborate with the IEEE Education & Healthcare Facilities Committee in assisting the US Army Corps of Engineers in gathering power system data from education communities that will inform statistical solutions for enhancing power system reliability for the Homeland.

United States Army Corps Power Relability Enhancement Program Flyer No. 1

United States Army Corps Power Reliability Enhancement Program Flyer No. 2

We maintain status information about this project — and all projects that enhance the reliability of education community power reliability — on the standing agenda of our periodic Power, Risk and Security colloquia. See our CALENDAR for the next online meeting; open to everyone

Issue: [19-156]

Category: Power, Data, Security

Colleagues: Mike Anthony, Robert G. Arno, Mark Bunal, Jim Harvey, Jerry Jimenez, Paul Kempf. Richard Robben

War Memorials

This content is accessible to paid subscribers. To view it please enter your password below or send mike@standardsmichigan.com a request for subscription details.

Military

“The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him,

but because he loves what is behind him.”

— G.K. Chesterton

The United States military academies incorporate by reference nearly all of the codes and standards that provide the templates for safety and sustainability of all other education communities. Where possible today we will examine a few noteworthy exceptions required by the United States Military.

Our approach is necessarily educational because military standards tend to be sensitive and product oriented and are frequently released for public consultation; except when the Department of Defense seeks competitive bids for products, systems or research projects. The bibliography linked below provides the broad contours of the topic.

NIST: Learn How to Find Standards

ASSIST: Database for Military Specifications

Defense Standardization Program

University of Minnesota Duluth: MIL-SPECS

Penn State University: US Government and Military Standards

Use the login credentials at the upper right of our home page to join the colloquium.

Commencement 1865 / John Ruskin

“…All the pure and noble arts of peace are founded on war; no great art ever yet rose on Earth, but among a nation of soldiers. There is no art among a shepherd people if it remains at peace. There is no art among an agricultural people if it remains at peace. Commerce is barely consistent with fine art, but cannot produce it. Manufacture not only is unable to produce it, but invariably destroys whatever seeds of it exist. There is no great art possible to a nation but that which is based on battle.

Now, though I hope you love fighting for its own sake, you must, I imagine, be surprised at my assertion that there is any such good fruit of fighting. You supposed, probably, that your office was to defend the works of peace, but certainly not to found them; nay, the common course of war, you may have thought, was only to destroy them. And truly I, who tell you this of the use of war, should have been the last of men to tell you so, had I trusted my own experience only.

Yet the conclusion is inevitable, from any careful comparison of the states of great historic races at different periods. The first dawn of it is in Egypt; and the power of it is founded on the perpetual contemplation of death, and of future judgment, by the mind of a nation of which the ruling caste were priests, and the second, soldiers. The greatest works produced by them are sculptures of their kings going out to battle or receiving the homage of conquered armies.

All the rudiments of art, then, and much more than the rudiments of all science, are laid first by this great warrior-nation, which held in contempt all mechanical trades, and in absolute hatred the peaceful life of shepherds. From Egypt art passes directly into Greece, where all poetry, and all painting, are nothing else than the description, praise, or dramatic representation of war, or of the exercises which prepare for it, in their connection with offices of religion. All Greek institutions had first respect to war, and their conception of it, as one necessary office of all human and divine life, is expressed simply by the images of their guiding gods. Apollo is the god of all wisdom of the intellect; he bears the arrow and the bow before he bears the lyre. Athena is the goddess of all wisdom in conduct. It is by the helmet and the shield, oftener than by the shuttle, that she is distinguished from other deities.

There were, however, two great differences in principle between the Greek and the Egyptian theories of policy. In Greece there was no soldier caste; every citizen was necessarily a soldier. And, again, while the Greeks rightly despised mechanical arts as much as the Egyptians, they did not make the fatal mistake of despising agricultural and pastoral life, but perfectly honored both. These two conditions of truer thought raise them quite into the highest rank of wise manhood that has yet been reached, for all our great arts, and nearly all our great thoughts, have been borrowed or derived from them. Take away from us what they have given, and I hardly can imagine how low the modern European would stand.

Now, you are to remember, in passing to the next phase of history, that though you must have war to produce art, you must also have much more than war—namely, an art-instinct or genius in the people; and that, though all the talent for painting in the world won’t make painters of you, unless you have a gift for fighting as well, you may have the gift for fighting, and none for painting. Now, in the next great dynasty of soldiers, the art-instinct is wholly wanting. I have not yet investigated the Roman character enough to tell you the causes of this, but I believe, paradoxical as it may seem to you, that, however truly the Roman might say of himself that he was born of Mars, and suckled by the wolf, he was nevertheless, at heart, more of a farmer than a soldier. The exercises of war were with him practical, not poetical; his poetry was in domestic life only, and the object of battle, pacis imponere morem. And the arts are extinguished in his hands, and do not rise again, until, with Gothic chivalry, there comes back into the mind of Europe a passionate delight in war itself, for the sake of war. And then, with the romantic knighthood which can imagine no other noble employment—under the fighting kings of France, England, and Spain—and under the fighting dukeships and citizenships of Italy, art is born again, and rises to her height in the great valleys of Lombardy and Tuscany, through which there flows not a single stream, from all their Alps or Apennines, that did not once run dark red from battle, and it reaches its culminating glory in the city which gave to history the most intense type of soldiership yet seen among men—the city whose armies were led in their assault by their king, led through it to victory by their king, and so led, though that king of theirs was blind, and in the extremity of his age.

And from this time forward, as peace is established or extended in Europe, the arts decline. They reach an unparalleled pitch of costliness, but lose their life, enlist themselves at last on the side of luxury and various corruption, and, among wholly tranquil nations, wither utterly away, remaining only in partial practice among races who, like the French and us, have still the minds, though we cannot all live the lives, of soldiers.

“It may be so,” I can suppose that a philanthropist might exclaim. “Perish then the arts, if they can flourish only at such a cost. What worth is there in toys of canvas and stone, if compared to the joy and peace of artless domestic life?” And the answer is—truly, in themselves, none. But as expressions of the highest state of the human spirit, their worth is infinite. As results they may be worthless, but, as signs, they are above price. For it is an assured truth that, whenever the faculties of men are at their fullness, they must express themselves by art; and to say that a state is without such expression, is to say that it is sunk from its proper level of manly nature. So that, when I tell you that war is the foundation of all the arts, I mean also that it is the foundation of all the high virtues and faculties of men.

SELECTIONS FROM THE WORKS OF JOHN RUSKIN

Chauncy B. Tinker, Ph.D

Professor of English at Yale College

New update alert! The 2022 update to the Trademark Assignment Dataset is now available online. Find 1.29 million trademark assignments, involving 2.28 million unique trademark properties issued by the USPTO between March 1952 and January 2023: https://t.co/njrDAbSpwB pic.twitter.com/GkAXrHoQ9T

— USPTO (@uspto) July 13, 2023

Standards Michigan Group, LLC

2723 South State Street | Suite 150

Ann Arbor, MI 48104 USA

888-746-3670