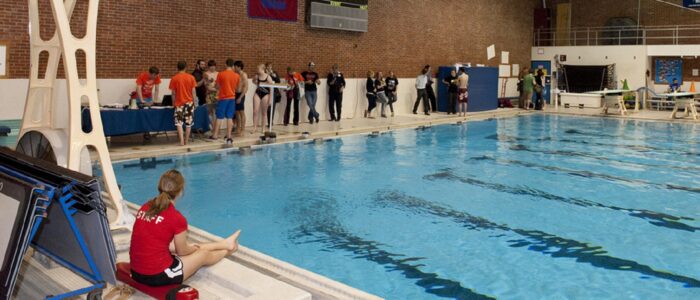

Education communities provide a large market for recreational and therapeutic water technology suppliers. Some of the larger research universities have dozens of pools including those in university-affiliated healthcare facilities. Apart from publicly visible NCAA swimming programs there are whirpools in healthcare facilities and therapeutic tubs for athletes in other sports. Ownership of these facilities requires a cadre of conformance experts to assure water safety.

NSF International is one of the first names in this space and has collaborated with key industry stakeholders to make pools, spas and recreational water products safer since 1949. The parent document in its suite is NSF 50 Pool, Spa and Recreational Water Standards which covers everything from pool pumps, strainers, variable frequency drives and pool drains to suction fittings, grates, and ozone and ultraviolet systems.

The workspace for this committee is linked below:

Joint Committee on Recreational Water Facilities

(Standards Michigan is an observer on this and several other NSF committees and is the only “eyes and ears” for the user interest; arguably the largest market for swimming pools given their presence in schools and universities.)

There are 14 task groups that drill into specifics such as the following:

Chemical feeders

Pool chemical evaluation

Flotation systems

Filters

Water quality

Safety surfacing

The meeting packet is confidential to registered attendees. You may communicate directly with the NSF Joint Committee Chairperson, Mr. Tom Vyles (admin@standards.nsf.org) about arranging direct access as an observer or technical committee member.

Almost all ANSI accredited technical committees have a shortage of user-interests (compliance officers, manufacturers and installers usually dominate). We encourage anyone in the education facility industry paying the bill for the services of compliance officers, manufacturers and installers to participate.

We maintain this title on the standing agenda of our Water and Sport colloquia. See our CALENDAR for the next onine meeting; open to everyone.

Issue: [13-89]

Category: Water, Sport

Colleagues: Mike Anthony, Ron George, Larry Spielvogel

More

IAPMO Swimming Pool & Spa Standards

UL 1081 Standard for Swimming Pool Pumps, Filters, and Chlorinators | (UL Standards tend to be product standards so we rank them lower in our priority ranking than interoperability standards.)