Parent Accommodation

- Home Page 24

Pork Chops with Red Cabbage and Pears

This content is accessible to paid subscribers. To view it please enter your password below or send mike@standardsmichigan.com a request for subscription details.

Morning Porridge

Porridge is a dish made by boiling grains, legumes, or starchy plants like oats, rice, cornmeal, or barley in water or milk until it reaches a soft, thick, and creamy consistency. It’s often eaten as a breakfast food and can be sweetened with sugar, honey, or fruit, or flavored with spices and other ingredients.

Common examples include oatmeal, rice porridge (like congee), and millet porridge. The specific ingredients and preparation vary widely across cultures and regions.

Not to be confused with grits; a specific type of porridge made from corn, with a distinct texture and cultural role, while porridge is a broader category encompassing many grains and preparations.

It was a work of love for Sir Roger. pic.twitter.com/mAHqCcYE4B

— Adam Krell (@adamkrell) November 24, 2025

High Altitude Cinnamon Rolls & Cowboy Coffee

Net Position 2024: $1.304B (Page 22)

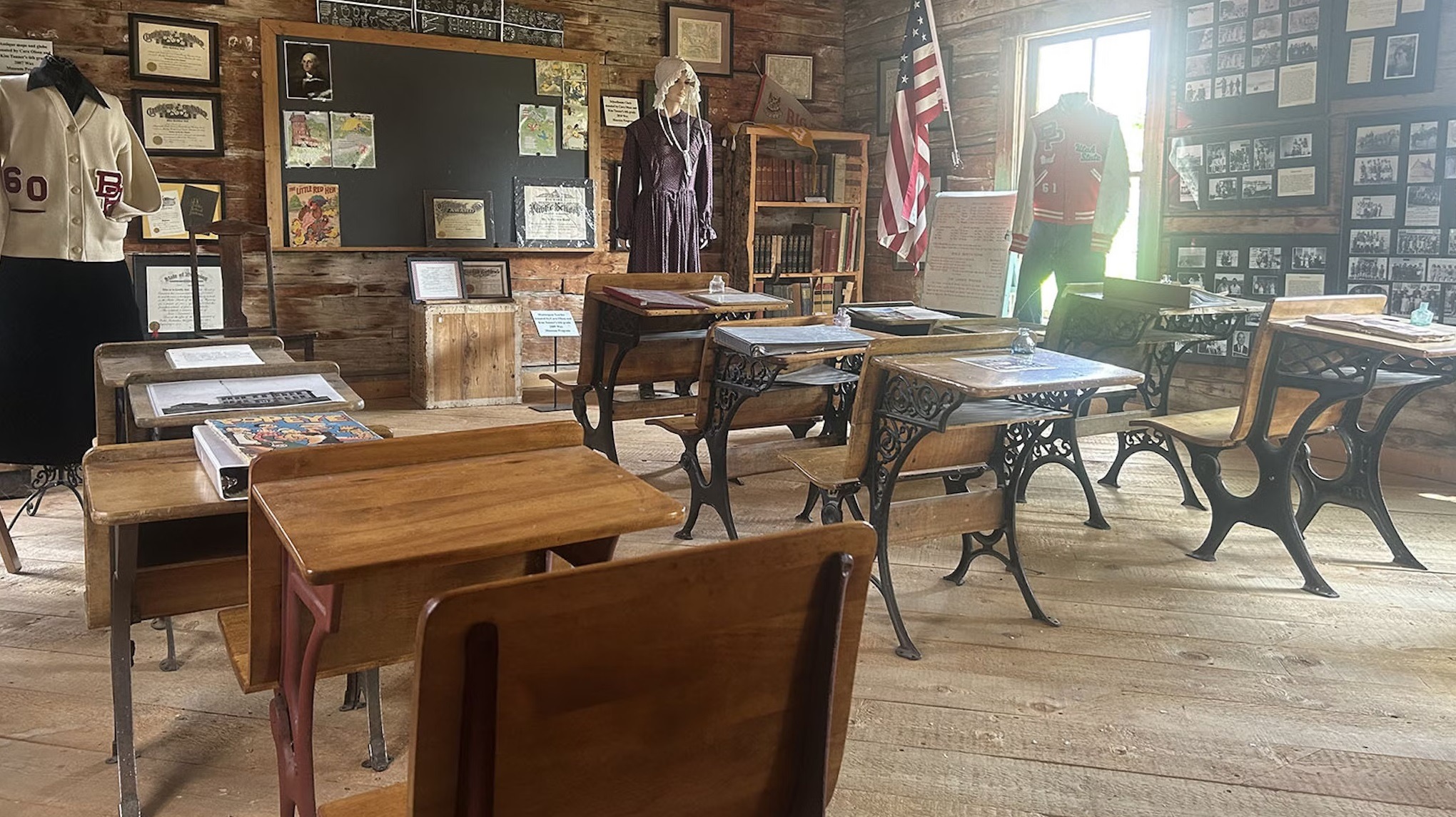

Old Main | 2021 Wyoming Building Code

Classes are underway at the University of Wyoming! Whether this is your first day of classes or the last time you’re starting your year as a Cowboy, good luck and we’re proud of all the hard work our Cowboys put in!#uwyo #TheWorldNeedsMoreCowboys #IAmACowboy #GoWyo #GoPokes pic.twitter.com/sev8I2pb8q

— University of Wyoming College of Arts & Sciences (@UWArtsSciences) August 22, 2022

“Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail” | 1921 Theodore Roosevelt

Interlochen

This content is accessible to paid subscribers. To view it please enter your password below or send mike@standardsmichigan.com a request for subscription details.

Cinnamon Banana Pancakes

NDSU Net Position 2024: $570 M | Standards North Dakota | Capital Renewal Master Plan

Due to expected weather conditions, North Dakota State University Fargo campus locations will be closed Thursday, December 18.

Classes are canceled and offices are closed. NDSU will resume normal operations on Friday, December 19.

Updates to this announcement will be made on… pic.twitter.com/EcwVoAKIwm

— North Dakota State University (@NDSU) December 18, 2025

Old Main, North Dakota Agricultural College | Milton Earl Beebe, Architect

This week, NDSU is hosting the state Future Farmers of America (FFA) convention with over 1,000 students from across North Dakota. We’re excited to have these future Bison on campus as students soon! 🤘🚜#NDSU pic.twitter.com/OoMmrpHim9

— North Dakota State University (@NDSU) June 5, 2024

“The Liberals are Coming, and They’re Bringing Fancy Coffee” https://t.co/XykfCFYZgVhttps://t.co/exHU6TR2h9

America is changed by flight from miserable Blue States to better Red States—only to import the policies that created the misery they fled from in the first place. pic.twitter.com/OaVVgrTxJr— Standards Michigan (@StandardsMich) October 31, 2022

This week, NDSU is hosting the state Future Farmers of America (FFA) convention with over 1,000 students from across North Dakota. We’re excited to have these future Bison on campus as students soon! 🤘🚜#NDSU pic.twitter.com/OoMmrpHim9

— North Dakota State University (@NDSU) June 5, 2024

Breaded Pork Tenderloin Sandwich

This content is accessible to paid subscribers. To view it please enter your password below or send mike@standardsmichigan.com a request for subscription details.

Kavárna u Rotlevů

“Bureaucracy is the death of any achievement”

ISO: National Standards of the Czech Republic

UNMZ Czech Office for Standards, Metrology, and Testing

🎽 What do our students Eliška Martínková and Eduard Kubelík compete in?

🎥 They will tell you in our reel. pic.twitter.com/Tev5jZ6Vn1

— Charles University (@CharlesUniPRG) August 10, 2024

Eggs Benedict & Cowboy Coffee

Standards Wyoming | Kitchen Standards

Weekly Construction Report: January 9-15

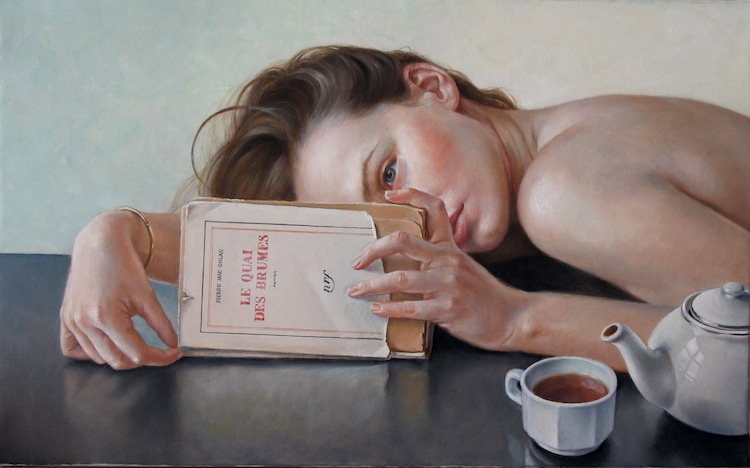

“A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste” — Pierre Bourdieu, Harvard University Press 1984

Cowboy Coffee | Appetite for Knowledge

Vicki Hayman, University of Wyoming Extension Nutrition Educator, explains how to put together an English muffin, poached egg, Canadian bacon, and a homemade hollandaise sauce named after Lemuel Benedict, a Wall Street banker who, in 1894, ordered a hangover remedy at the Waldorf Hotel in New York. He requested buttered toast, poached eggs, crisp bacon, and hollandaise sauce.

The hotel’s maître d’hôtel, Oscar Tschirky, was impressed and adapted the dish for the menu, swapping bacon for ham and toast for an English muffin, naming it Eggs Benedict in his honor. Another claim links it to Commodore E.C. Benedict, but the Lemuel story is more widely accepted. The dish’s luxurious combination of poached eggs, ham, English muffin, and hollandaise sauce cemented its fame as a breakfast classic.

Lemon Ginger Tea

Statement of Net Position 2024: $1.251B (Page 9)

Planning, Design & Construction Management: 2025-2026 Institutional Priorities

IEEE: Water Purification for Human Consumption

Elon University Facilities Management

For the 20th year, Elon University has been recognized as a leader in study abroad by the Institute of International Education. Elon is ranked #1 in the percentage of undergraduate students who participate in study abroad among doctoral universities. https://t.co/kak6mETp2Q pic.twitter.com/0m7fyJ4rzT

— Elon University (@elonuniversity) November 18, 2025

New update alert! The 2022 update to the Trademark Assignment Dataset is now available online. Find 1.29 million trademark assignments, involving 2.28 million unique trademark properties issued by the USPTO between March 1952 and January 2023: https://t.co/njrDAbSpwB pic.twitter.com/GkAXrHoQ9T

— USPTO (@uspto) July 13, 2023

Standards Michigan Group, LLC

2723 South State Street | Suite 150

Ann Arbor, MI 48104 USA

888-746-3670