Category Archives: Architectural/Hammurabi

- Home

- Archive by category "Architectural/Hammurabi" (Page 7)

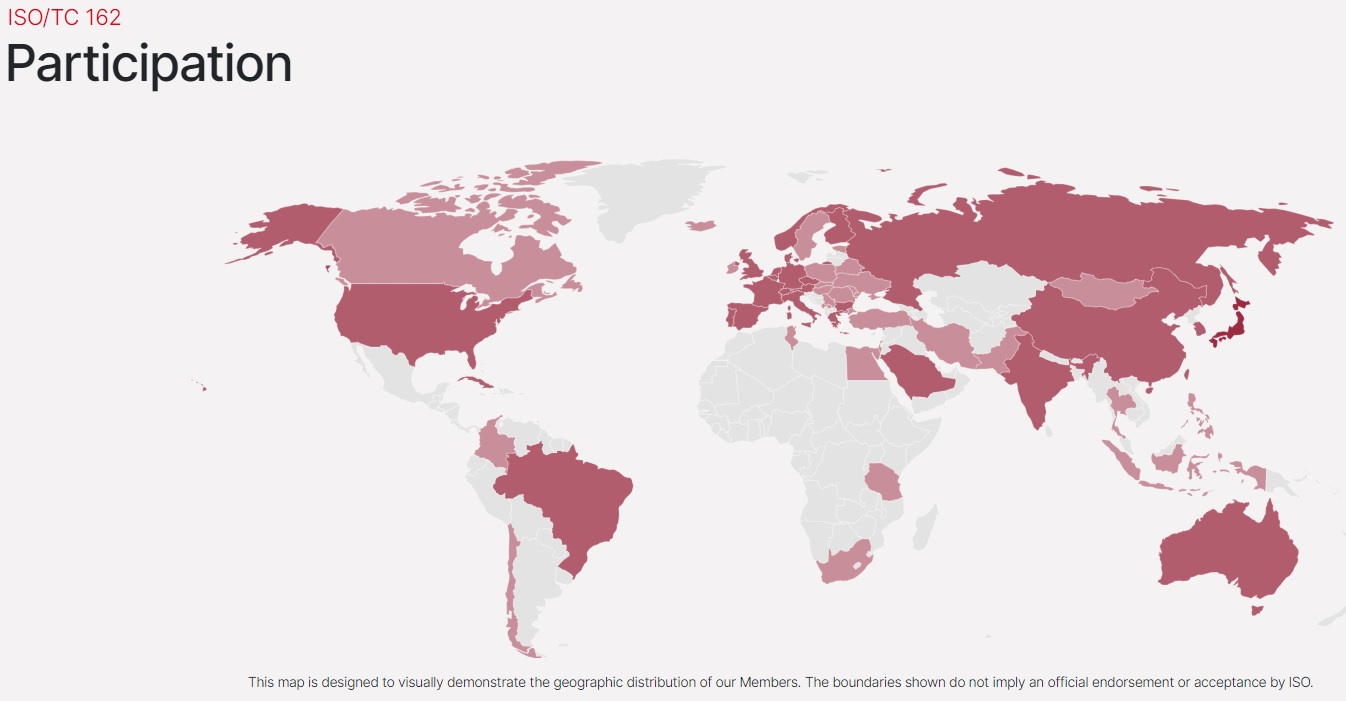

Doors, windows and curtain walling

Scope: Standardization in the field of doors, doorsets, windows, and curtain wall including hardware, manufactured from any suitable material covering the specific performance requirements, terminology, manufacturing sizes and dimensions, and methods of test. The Japanese Engineering Standards Committee is the Global Secretariat.

Multinational manufacturing and trade in the door manufacturing industry involve the production, distribution, and sale of doors across international borders. This industry encompasses a wide range of door types, including residential, commercial, industrial, and specialty doors. Here are some of the key fine points to consider in multinational manufacturing and trade within the door manufacturing sector:

- Global Supply Chains:

- Multinational door manufacturers often have complex global supply chains. Raw materials, components, and finished products may be sourced from various countries to optimize costs and quality.

- Regulatory Compliance:

- Compliance with international trade regulations and standards is crucial. This includes adhering to import/export laws, product safety regulations, and quality standards, such as ISO certifications.

- Market Segmentation:

- Different regions and countries may have varying preferences for door types, materials, and styles. Multinational manufacturers need to adapt their product offerings to meet local market demands.

- Distribution Networks:

- Establishing efficient distribution networks is essential. This involves selecting appropriate distribution channels, including wholesalers, retailers, and e-commerce platforms, in different countries.

- Tariffs and Trade Barriers:

- Import tariffs and trade barriers can significantly impact the cost of doing business across borders. Understanding and navigating these trade policies is essential for multinational door manufacturers.

- Localization:

- Multinational manufacturers often localize their products to suit the preferences and requirements of specific markets. This may involve language translation, customization of door designs, or adjustments to product dimensions.

- Quality Control:

- Ensuring consistent product quality across borders is critical for maintaining brand reputation. Implementing quality control processes and standards at all manufacturing locations is essential.

- Cultural Considerations:

- Understanding cultural nuances and local customs can help multinational manufacturers market their products effectively and build strong customer relationships.

- Logistics and Transportation:

- Efficient logistics and transportation management are essential for timely delivery of doors to international markets. This includes selecting appropriate shipping methods and managing inventory efficiently.

- Sustainability:

- Sustainability concerns, such as environmental impact and responsible sourcing of materials, are becoming increasingly important in the door manufacturing industry. Multinational manufacturers may need to comply with different environmental regulations in various countries.

- Intellectual Property:

- Protecting intellectual property, including patents and trademarks, is crucial in a global market. Manufacturers must be vigilant against counterfeiting and IP infringement.

- Market Research:

- Conducting thorough market research in each target country is essential. This includes understanding local competition, pricing dynamics, and consumer preferences.

- Risk Management:

- Multinational manufacturing and trade involve various risks, including currency fluctuations, political instability, and supply chain disruptions. Implementing risk mitigation strategies is vital for long-term success.

In summary, multinational manufacturing and trade in the door manufacturing industry require a comprehensive understanding of global markets, regulatory compliance, cultural differences, and logistics. Successfully navigating these complexities can help manufacturers expand their reach and compete effectively in a globalized world.

Relevant agencies:

ASTM International: ASTM develops and publishes voluntary consensus standards used in various industries, including construction. ASTM standards cover materials, testing procedures, and specifications related to doors, windows, and associated components.

National Fenestration Rating Council (NFRC): NFRC is a U.S.-based organization that focuses on rating and certifying the energy performance of windows, doors, and skylights. They provide performance ratings and labels used by manufacturers to communicate product energy efficiency to consumers.

American Architectural Manufacturers Association (AAMA): AAMA is a U.S.-based organization that develops standards and specifications for windows, doors, and curtain walls. Their standards cover performance, design, and testing.

National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS): NIBS is involved in research, education, and the development of standards for the building and construction industry in the United States.

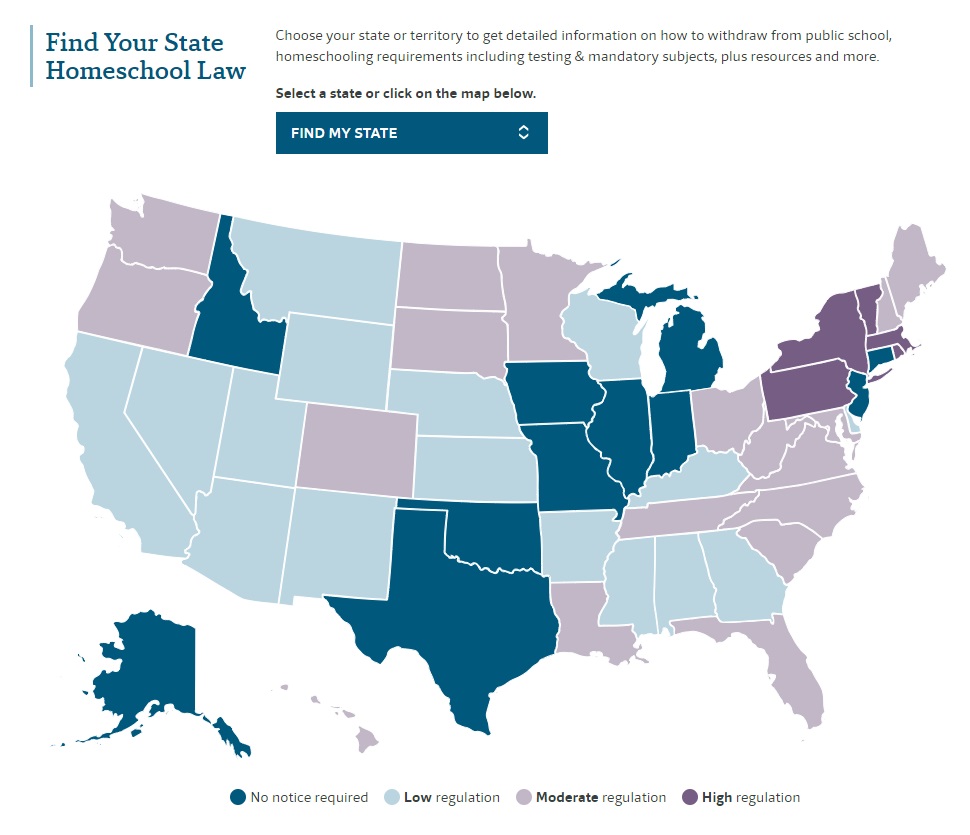

Homeschool Laws By State

Education happening outside the home offers several advantages that contribute to the holistic development of children:

Socialization: Interacting with peers and teachers in a structured environment helps children learn social skills, cooperation, and conflict resolution, which are essential for navigating the complexities of adult life.

Diverse Perspectives: Schools expose children to a variety of viewpoints, backgrounds, and cultures, fostering tolerance, empathy, and understanding of diversity.

Specialized Instruction: Qualified educators are trained to teach specific subjects and tailor instruction to different learning styles, ensuring that children receive a well-rounded education.

Access to Resources: Schools provide access to resources such as libraries, laboratories, sports facilities, and technology that may not be available at home, enriching the learning experience.

Extracurricular Activities: Schools offer extracurricular activities like sports, music, drama, and clubs, which help children discover their interests, develop talents, and build leadership skills.

Preparation for the Real World: Schools simulate real-world environments, teaching children important life skills such as time management, responsibility, and teamwork, which are crucial for success in adulthood.

Professional Development: Educators undergo continuous training and development to stay updated with the latest teaching methodologies and educational practices, ensuring high-quality instruction for students.

While home-based learning can complement formal education and offer flexibility, the structured environment and resources provided by schools play a vital role in shaping well-rounded individuals ready to thrive in society.

Federal architecture

This content is accessible to paid subscribers. To view it please enter your password below or send mike@standardsmichigan.com a request for subscription details.

Classroom Furniture

The Business and Institutional Furniture Manufacturers Association standards catalog — largely product (rather than interoperability oriented) is linked below:

In stabilized standards, it is more cost effective to run the changes through ANSI rather than a collaborative workspace that requires administration and software licensing cost. Accordingly, redlines for changes, and calls for stakeholder participation are released in ANSI’s Standards Portal:

STANDARDS ACTION WEEKLY EDITION

Send your comments to Dave Panning. (See Dave’s presentation to the University of Michigan in the video linked below.

We find a great deal of interest in sustainable furniture climbing up the value chain and dwelling on material selection and manufacture. We encourage end-users in the education industry — specifiers, department facility managers, interior design consultants, housekeeping staff and even occupants — to participate in BIFMA standards setting. You may obtain an electronic copies for in-process standards from David Panning, (616) 285-3963, dpanning@bifma.org You are encouraged to send comments directly to BIFMA (with copy to psa@ansi.org). David explains its emergent standard for furniture designed for use in healthcare settings in the videorecording linked below:

Contacts: Mike Anthony, Christine Fischer, Jack Janveja, Dave Panning

Category: Architectural, Facility Asset Management

Related:

A Guide to United States Furniture Compliance Requirements

New update alert! The 2022 update to the Trademark Assignment Dataset is now available online. Find 1.29 million trademark assignments, involving 2.28 million unique trademark properties issued by the USPTO between March 1952 and January 2023: https://t.co/njrDAbSpwB pic.twitter.com/GkAXrHoQ9T

— USPTO (@uspto) July 13, 2023

Standards Michigan Group, LLC

2723 South State Street | Suite 150

Ann Arbor, MI 48104 USA

888-746-3670