“Lord how this world improves as we grow older”

The Nature of Tomorrow: A History of the Environmental Future

Michael Rawson

In the nineteenth century, machines would become so central to the imagined future that no vision of tomorrow was credible without them. (The catalyst for this transformation was the Industrial Revolution.) The author Jane Webb displayed a keen appreciation for that fact in a popular work of fiction that she published in 1827. Her story, set in twenty-second-century Egypt, described the Nile valley as a place where “steamboats glided down the canals, and furnaces raised their smoky heads amidst groves of palm trees; whilst iron railways intersected orange groves, and plantations of dates and pomegranates might be seen bordering excavations intended for coal pits.” In Webb’s future Egypt, as in so many other visions of tomorrow produced in the first half of the nineteenth century, machines provided the muscle for developing the natural environment at a fantastic pace and on a global scale.

The futuristic fiction of the early nineteenth century overflowed with mechanical inventions. Airships carrying thousands of passengers dominate the skies; steamships, sometimes with additional pull from giant kites, turn the oceans into lakes; trains traveling hundreds of miles an hour defeat time. Machines dry hay faster, bore deeper tunnels, and shield cities from inclement weather. The more machines, the more futuristic the story felt. Jane Webb’s book was so packed with imaginative innovations in science and technology that the famous English landscape architect J.C. Loudon went out of his way to meet the author, assuming it was a man. They were married later that year.

Authors did not include fantastic machines in their tales of tomorrow just for their novelty value. The machines demonstrated human control of the natural world, something writers did not hesitate to point out. “So many new inventions had been struck out,” wrote Webb of her future England, “so many wonderful discoveries made, and so many ingenious contrivances put into execution, that poor Nature seemed to be degraded from her throne, and usurping man to have stepped up to supply her place.” The fiction of the future was in general agreement that machines would transform dreams of growth and progress into reality.

Most of those contemplating the future saw particular potential in steam, which was the most transformative technology of the day. Steam’s power to remold the material world and fuel expansion appeared to be boundless. When the great French scientist François Arago delivered an address to commemorate James Watt, who made important refinements to the steam engine, he foresaw a future liberated from the bonds of nature through steam. With such power at its command, he claimed, humankind could bring more land under cultivation, grow more food, increase its population, expand its cities, and cover the earth with elegant mansions, even those parts previously considered uninhabitable. Future generations, Arago assured his listeners, would remember this time as the Age of Watt.

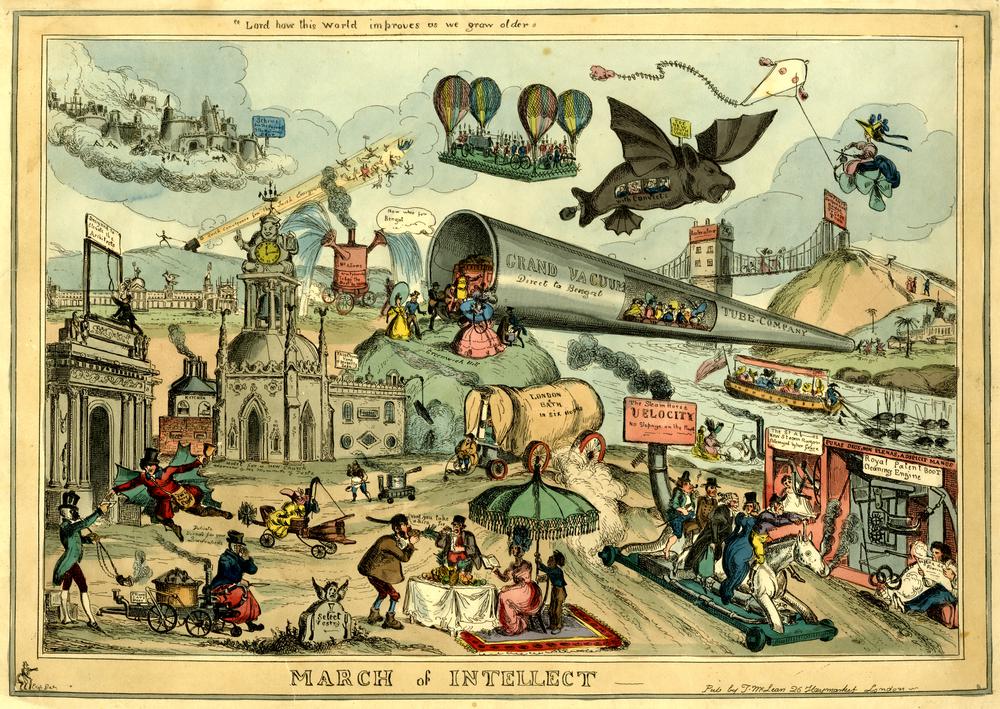

Possible applications for steam multiplied so quickly that, as early as the 1820s, parodies of future steam technologies began to appear. One future world sped up the delivery of mail by using steam-powered cannons to shoot it from town to town. Another featured a “steam concert” in which the performers were steam-powered machines that achieved greater technical accuracy than their human counterparts, and without being subject to “colds, loss of voice, and bronchitis.” Still another contained a ballroom that enabled guests to dance a quadrille without the trouble of having to move their feet: they simply stood on circles set into the floor (blue for the gentlemen, pink for the ladies) while the steam-powered circles moved them around in the necessary pattern.

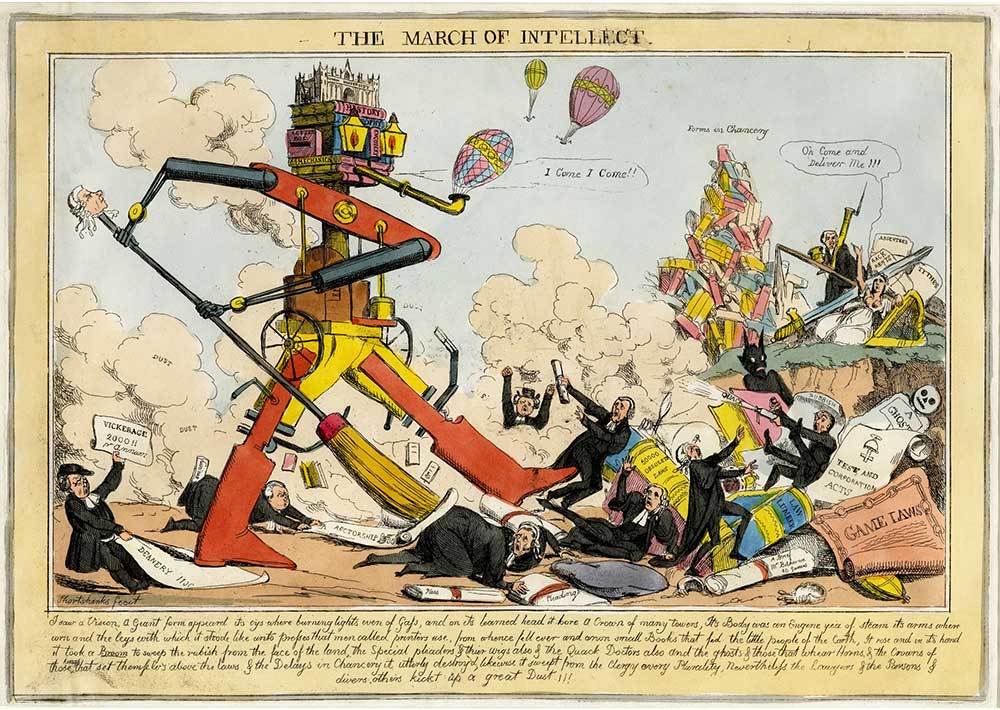

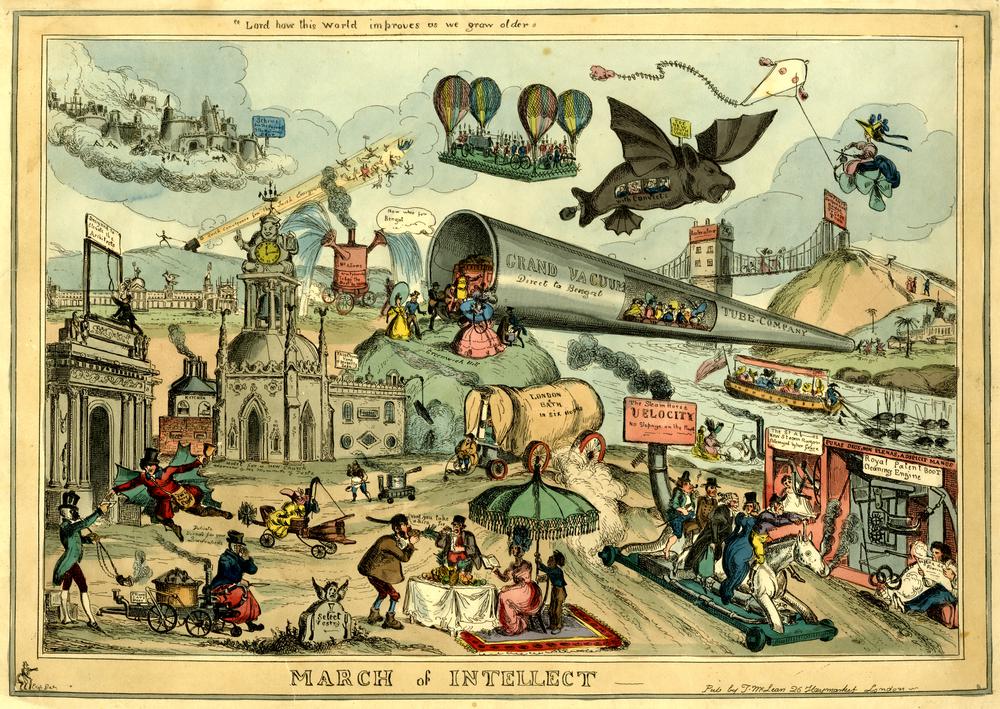

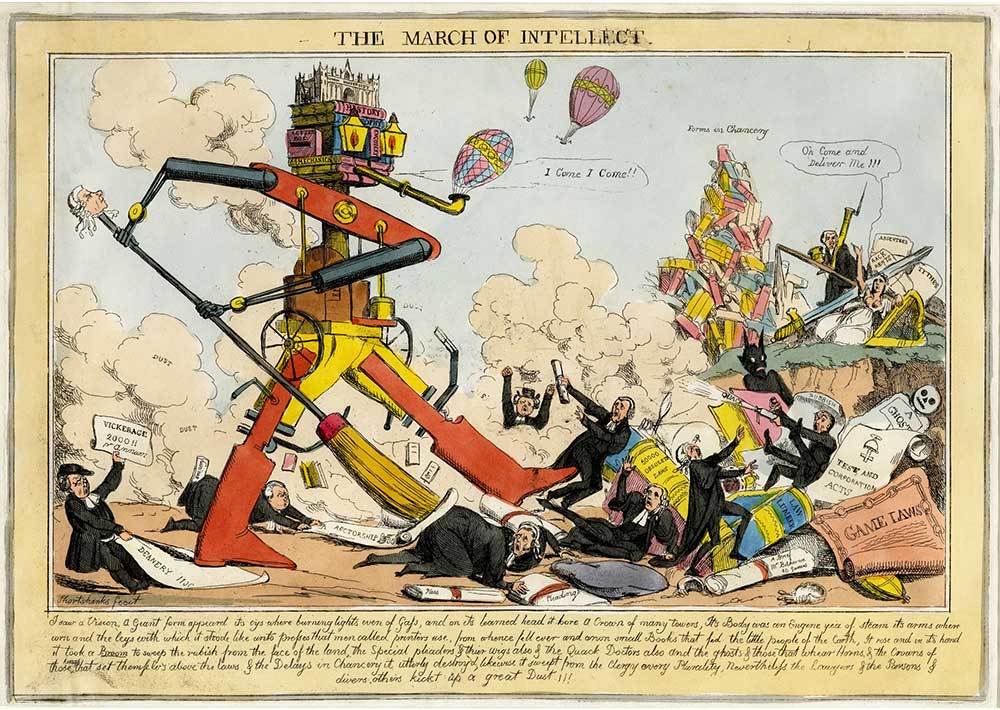

British illustrators joined in, projecting the cutting-edge technologies of the day into comical futures. Henry Alken’s images show the roads and parks of London crowded with a dizzying variety of fast-moving steam-powered vehicles that fill the air with smoke and occasionally run out of control or explode. Charles Jameson Grant’s image of the year 2000 depicts a long chain of movable houses traveling by rail and people making shorter trips using mechanical wings fastened to their backs. William Heath’s series of images shows a vacuum tube that provides a direct trip to India, a steam-powered horse long enough to accommodate five riders, and machines doing a variety of household chores. Most illustrators of future worlds filled the skies with every kind of aerial device imaginable, usually kept aloft by balloons, kites, steam, or some combination of the three.

The March of Intellect, by William Heath, c. 1828. © Trustees of the British Museum

Faith in the speed of technological change ran so high that the reading public could be easily fooled into believing advances had taken place that, in fact, had not. In April 1844 the New York Sun ran a front-page article claiming that a manned balloon had just made the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, and in a mere seventy-five hours. The article, a hoax written anonymously by Edgar Allan Poe, used convincing details from actual balloon voyages to describe a trip that would not actually take place until 1978. Steeped in the idea of progress and eager for stories of human advancement, much of the reading public—especially the more intelligent, thought Poe—accepted the account without question. So many people wanted copies of the paper, Poe later wrote, that “the whole square surrounding the Sun building was literally besieged.”

The fascination with new discoveries arose partly from the growing appreciation that applied or “useful” knowledge could enhance national power. As early as 1774 Great Britain began enacting laws preventing the export of cotton machinery, the golden goose of the British economy, and forbidding the emigration of artisans who knew how it worked. Later it became clear that the traditional sources of national power were undergoing a broader shift. “Henceforth,” wrote an American futurist in 1833, “it is no more the strength of the human arm, or the number of men, nor personal courage and bravery, nor the talents of military commanders, nor the advantages of geographical situations, that give power to a nation; but it is intelligence (knowledge of useful things).” The French utopian Claude-Henri de Saint-Simon would have agreed, as he looked forward to a day when the citizens of the world invested authority in a technocratic elite.

The true promise of industrialization and mechanization, however, was material abundance. There was widespread hope that the application of mechanized production to earth’s natural resources would produce so much material wealth that most of humanity’s problems would simply vanish. Why steal from others when goods were so cheap that they might as well be free? Why make war with another country when yours was awash in plenty? Why envy your neighbor when everyone could live the life of the rich? Why deal sharply to achieve wealth when it was readily at hand for everyone? In such a world, money and private property might become entirely unnecessary, and most conflicts would end before they began.

Promises of abundance appealed to both capitalists and utopian socialists, an early wave of socialist thinkers. The utopian socialists saw capitalism as a failure but were sold on the productive benefits of industrialization. In Britain, Robert Owen advocated the creation of model industrial communities in the countryside and believed that, if properly organized, industry could produce more wealth “than the population of the earth can require or advantageously use.” In France, Étienne Cabet began a popular movement based on the fictional utopia he portrayed in Travels in Icaria, assuring his readers that “the current and limitless productive power by means of steam and machines can assure equality of abundance.” Industrialization, if guided by a socialist society, could set humankind free.

Their socialist successors, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, also looked forward to a world of unprecedented material abundance driven by scientific and technological advances. But their prophecy of a communist future, which would become one of the most influential visions of tomorrow ever articulated, showed more awareness of the harmful environmental consequences of growth. They worried about soil exhaustion, forest depletion, water contamination, and air pollution; recognized the connection between exploiting workers and exploiting nature in the rush for development; and explicitly stated that humankind has a responsibility to hand the next generation an improved environment rather than a squandered one.

“The Lost Balloon” 1882 William Holbrook Beard | Smithsonian American Art Museum

Many of the utopian socialist futures also carried an implicit critique of consumption, the flipside of industrial production. Despite their wholehearted embrace of the factory, Cabet and Owen foresaw simple material lives, though not nearly as spartan as in the earlier scientific utopias. The French utopian socialist Charles Fourier, who was far less enamored of industrial expansion, attacked the growing consumer culture more directly. He rejected the dominant economic idea that “if every individual could be made to use four times as much clothing as he does, society would quadruple the wealth it derives from manufacturing work.” Instead Fourier hoped to keep consumption low by, first, shifting from individual household consumption to more efficient communal consumption (a move that he believed would also reduce waste) and, second, producing manufactured goods of such a high quality that they would rarely need to be replaced. Although industrialization would help to ensure that everyone had enough, consumption was rarely an end in itself in the socialist utopias.

The same was not true in capitalist circles, where increased consumption came to have a far more positive connotation. By mid-century, economists had built their understanding of resource use on the assumption that human wants are unlimited. That idea, combined with the expectation of boundless plenty through continued growth, suggested that increasing personal consumption was a positive good that would promote progress. “The number of artificial wants amongst a people,” wrote the London author and barrister Michael Angelo Garvey, “and the estimate they form of what constitutes comfort, are the infallible measure of their advance from barbarism.” As a result, any attempt to suppress material wants was “a monstrous error” that would “extinguish science, destroy all the arts by starvation, put an end to commerce, and erase every vestige of civilization from the face of the earth.” Growth-driven consumption became associated with civilization and self-denial with savagery, helping to drive the West away from the classic utopia of sufficiency and toward a new utopian vision of abundance.

Michael Rawson is a professor of history at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. He is the author of The Nature of Tomorrow: A History of the Environmental Future and Eden on the Charles: The Making of Boston, which was the recipient of numerous awards and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

CLICK HERE to order complete book