“We worry about what a child will become tomorrow,

yet we forget that he is someone today.”

– Stacia Tauscher

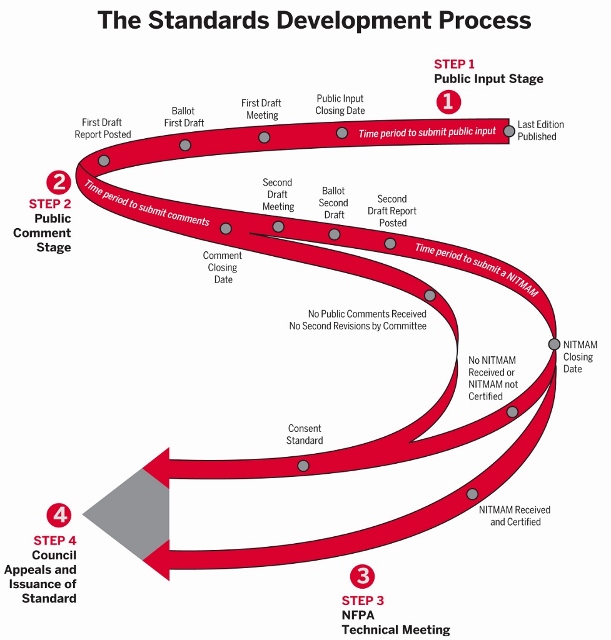

Today we run a status check on the stream of technical and management standards evolving to assure the highest possible level of security in education communities. The literature expands significantly from an assortment of national standards-setting bodies, trade associations, ad hoc consortia and open source standards developers. CLICK HERE for a sample of our work in this domain.

School security is big business in the United States. According to a report by Markets and Markets, the global school and campus security market size was valued at USD 14.0 billion in 2019 and is projected to reach USD 21.7 billion by 2025, at a combined annual growth rate of 7.2% during the forecast period. Another report by Research And Markets estimates that the US school security market will grow at a compound annual growth rate of around 8% between 2020 and 2025, driven by factors such as increasing incidents of school violence, rising demand for access control and surveillance systems, and increasing government funding for school safety initiatives.

Because the pace of the combined annual growth rate of the school and campus security market is greater than the growth rate of the education “industry” itself, we’ve necessarily had to break down our approach to this topic into modules:

Security 100. A survey of all the technical and management codes and standards for all educational settings — day care, K-12, higher education and university affiliated healthcare occupancies.

Security 200. Queries into the most recent public consultations on the components and interoperability* of supporting technologies

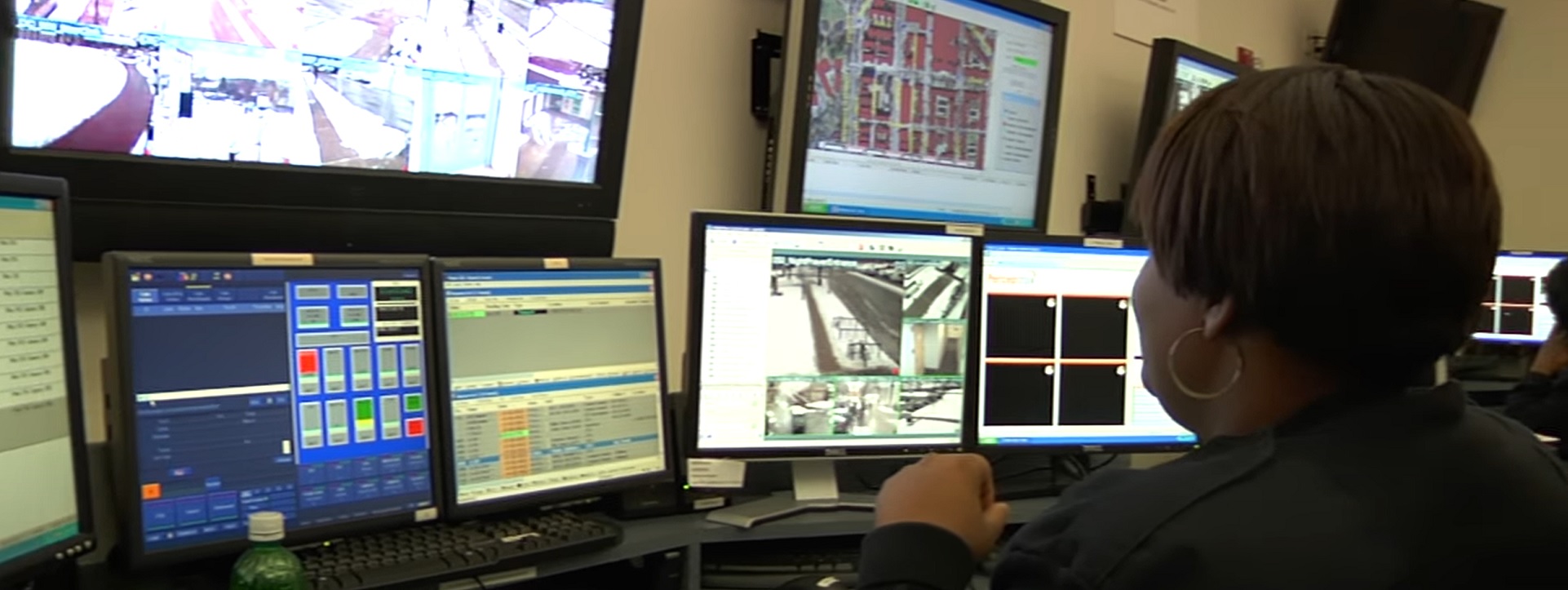

Video surveillance: indoor and outdoor cameras, cameras with night vision and motion detection capabilities and cameras that can be integrated with other security systems for enhanced monitoring and control.

Access control: doors, remote locking, privacy and considerations for persons with disabilities.

Panic alarms: These devices allow staff and students to quickly and discreetly alert authorities in case of an emergency.

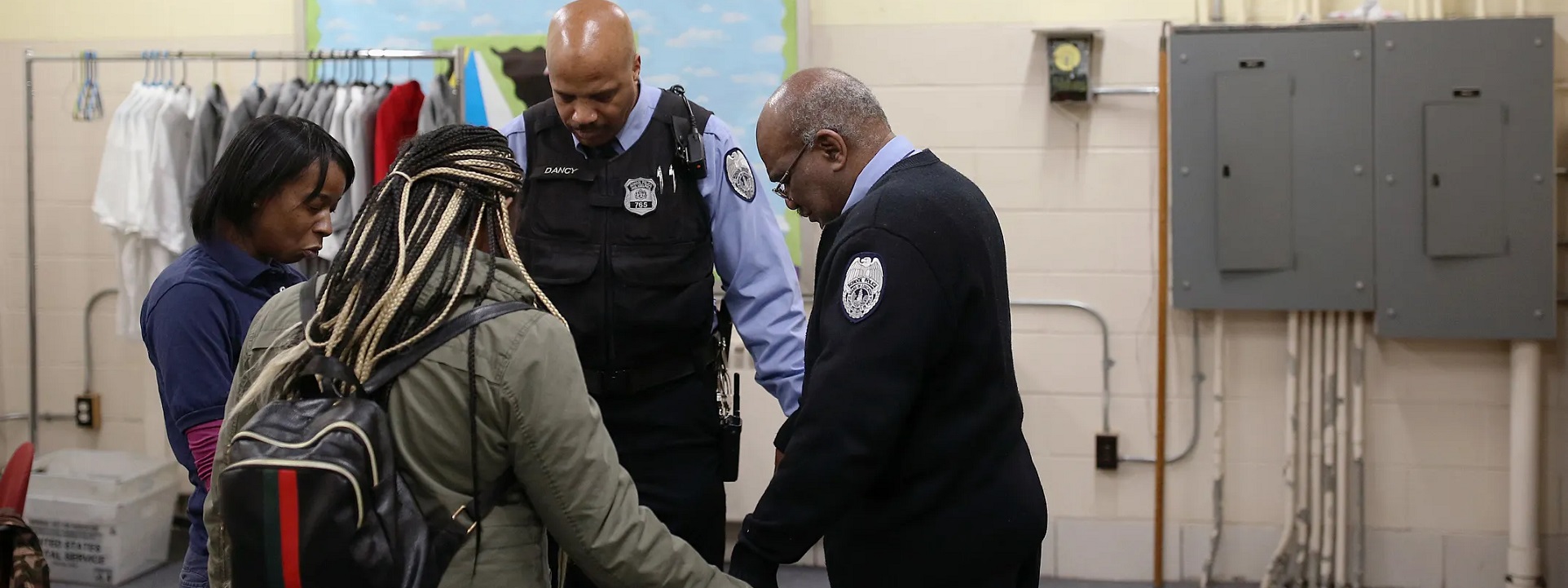

Metal detectors: These devices scan for weapons and other prohibited items as people enter the school.

Mass notification systems: These systems allow school administrators to quickly send emergency alerts and notifications to students, staff, and parents.

Intrusion detection systems: These systems use sensors to detect unauthorized entry and trigger an alarm.

GPS tracking systems: These systems allow school officials to monitor the location of school buses and track the movements of students during field trips and other off-campus activities.

Security 300. Regulatory and management codes and standards; a great deal of which are self-referencing.

Security 400. Advanced Topics. NFPA 731 Standard for the Installation of Premises Security Systems

As always, we reckon first cost and long-term maintenance cost, including software maintenance for the information and communication technologies (i.e. anything with wires) installed in the United States. Cybersecurity is outside our wheelhouse and beyond our expertise. In order to do any of the foregoing reasonably well, we have to leave cybersecurity standards to others.

Builders Hardware Manufacturers Association

Education Community Safety catalog is one of the fast-growing catalogs of best practice literature. In developing district security plans, K-12 school leaders stress that school safety is a cross-functional responsibility and every individual’s participation drives the success of overall safety protocols. We link a small sample below and update ahead of every Security colloquium.

Artificial Intelligence Tries (and Fails) to Detect Weapons in School

Could AI be the future of preventing school shootings?

Executive Order 13929 of June 16, 2020 Safe Policing for Safe Communities

National Center for Education Statistics: School Safety and Security Measures

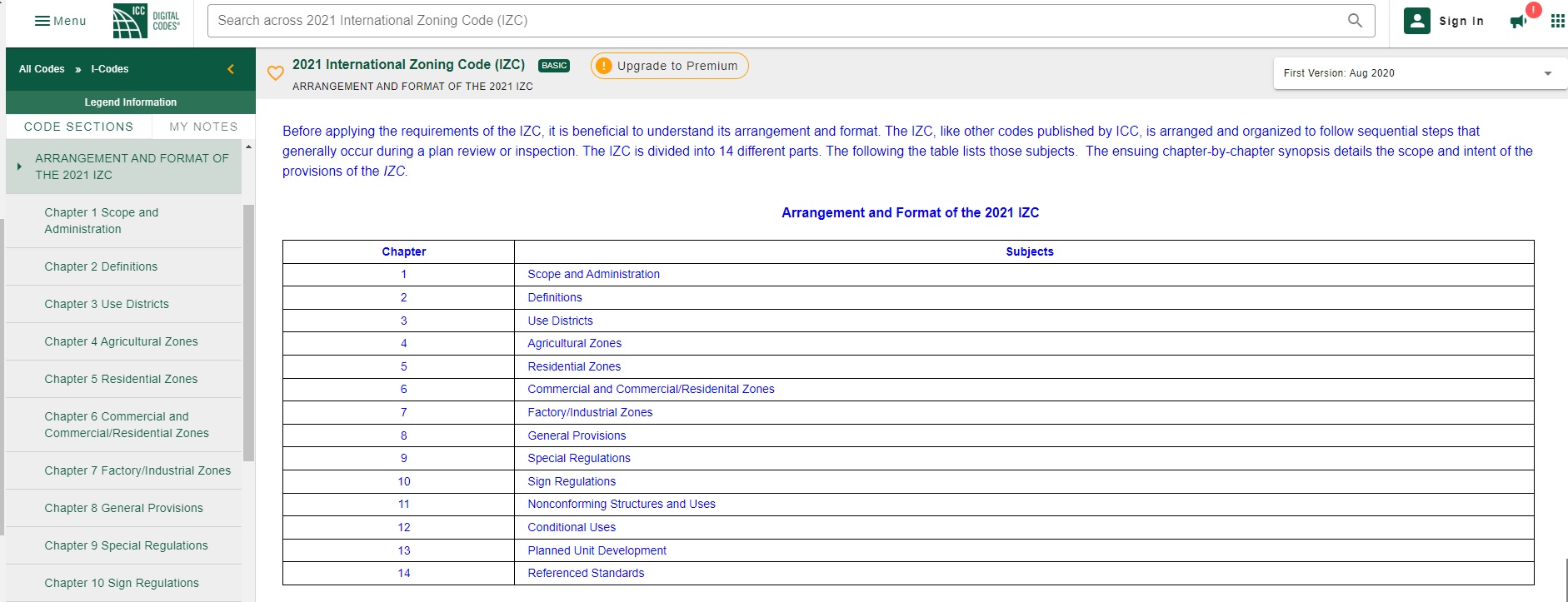

International Code Council

2021 International Building Code

Section 1010.1.9.4 Locks and latches

Section 1010.2.13 Delayed egress.

Section 1010.2.14 Controlled egress doors in Groups I-1 and I-2.

Free Access: NFPA 72 National Fire Alarm and Signaling Code

Free Access: NFPA 731 Standard for the Installation of Premises Security Systems

IEEE: Design and Implementation of Campus Security System Based on Internet of Things

APCO/NENA 2.105 Emergency Incident Data Document

C-TECC Tactical Emergency Casualty Care Guidelines

Department of Transportation Emergency Response Guidebook 2016

NENA-STA-004.1-2014 Next Generation United States Civic Location Data Exchange Format

Example Emergency Management and Disaster Preparedness Plan (Tougaloo College, Jackson, Mississippi)

Partner Alliance for Safer Schools

Federal Bureau of Investigation Academia Program

Most Dangerous Universities in America

Federal Bureau of Investigation: Uniform Crime Reporting Program

* Interoperability refers to the ability of different technologies or systems to communicate and work together seamlessly. In the context of school security technologies, interoperability can help improve the effectiveness of security systems and make it easier for school personnel to manage and respond to potential security threats. Here’s what we look for:

- Standardization: By standardizing communication protocols and data formats, school security technologies can be made more compatible with each other, making it easier for different systems to communicate and share information.

- Integration: School security technologies can be integrated with each other to provide a more comprehensive security solution. For example, access control systems can be integrated with video surveillance systems to automatically trigger alerts when an unauthorized person enters a restricted area.

- Open Architecture: Open architecture solutions enable different security systems to be connected and communicate with each other regardless of their manufacturer or supplier. This approach makes it easier to integrate different technologies and avoid vendor lock-in.

- Cloud-based Solutions: Cloud-based security solutions can enable interoperability by providing a centralized platform for managing and monitoring different security systems. This approach can also simplify the deployment of security technologies across multiple locations.

- Collaboration: School security technology providers can work together to develop interoperability standards and best practices that can be adopted across the industry. Collaboration can help drive innovation and improve the effectiveness of security systems.